FREEPORT – Marilyn Davis is steeling her heart. The last time she did laundry, she set aside a dirty T-shirt and pair of socks that belong to her grandson. They carry his scent. Now everything of his is precious.

These women, and their close-knit community on Grand Bahama Island, are caught in the middle of a mystery that has gripped their country and attracted the attention of law enforcement from South Florida and beyond. In the past five months, five boys have vanished from the Freeport area, one by one, without a trace.

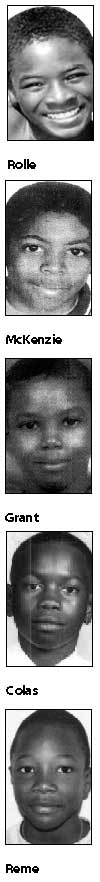

The first, Jake Grant, 12, left his home May 9, telling his sister he'd be right back. Mackinson Colas, then 11, was sent on a short errand by his mother May 16. Deangelo McKenzie, 13, left for school the morning of May 27, and hasn't been seen since. Junior Reme, 11, disappeared July 29. Desmond Rolle, 14, vanished after leaving his part-time job at Winn Dixie one week ago today.

The first, Jake Grant, 12, left his home May 9, telling his sister he'd be right back. Mackinson Colas, then 11, was sent on a short errand by his mother May 16. Deangelo McKenzie, 13, left for school the morning of May 27, and hasn't been seen since. Junior Reme, 11, disappeared July 29. Desmond Rolle, 14, vanished after leaving his part-time job at Winn Dixie one week ago today.

On this island known for its beautiful beaches and friendly, easy-going locals, people are full of fear and, increasingly, anger.

"At first, we just thought we were dealing with a runaway," recalls a staunch but tired-looking Officer Basil Rahming, the police press liaison. "Five months later, we do not know what has happened. We don't know if they are dead or alive. We have searched the island. We have detained [and released] about 25 persons for questioning. We're working without a crime scene."

He pauses and sighs, "We've never had anything like this happen in the history of this country. This is unprecedented and unacceptable."

Members of the FBI, Scotland Yard and the Broward County Sheriff's Office have offered their expertise and helped create suspect profiles. One common thread in the cases: all five children worked as bag boys at the same Winn-Dixie, a casual arrangement in which they earned only customer tips. They also frequented a game room across the street from the supermarket.

"It doesn't seem to be coincidental they all worked there," is all Rahming will say.

One man, picked up Wednesday night, remains in police custody but has not been charged. Officials say they plan more arrests in upcoming days, but won't say more, citing fear of jeopardizing the case — and fear of what the community might do to any innocent person mistakenly associated with the disappearances.

But police cannot hold their current suspect indefinitely, having already been granted one four-day extension by the courts.

The clock is ticking.

All the while, the mystery nags at the residents of Grand Bahama, an island about 100 miles long and seven miles wide, home to about 60,000 people, most living in Freeport.

All five boys lived within several miles of each other, some within walking distance. This tragedy is in everyone's back yard.

Volunteers search door to door, neighbors hand out flyers, churches hold candlelight vigils and special prayer services. Each time another child vanishes, these rituals begin anew.

Freeport, residents say, has long been a place where young children stayed out playing late and parents didn't worry. Now, some mothers won't let their children outside. Video arcades have agreed not to allow children under 17 to stay past 8 p.m., unless they are with an adult.

In the absence of fact, rumors have swept the island. Police struggle to quell them.

"We've heard many theories, ranging from sexual predators, child stealers, persons who may have been involved in the slave market in other countries, stealing organs," Rahming said.

Police have yet to find evidence of any of these things, but still the speculation persists.

On Thursday, one of the latest rumors erupted: that police had searched the Winn-Dixie freezer and found body parts. Hundreds of people spontaneously rushed from their homes and jobs and gathered in front of the supermarket, an impromptu horde of worry and pain and frustration. There never were any body parts.

That, in a sick sort of way, would have at least been progress, some frustrated residents say.

"I'm waiting and hoping and praying to hear what has happened. Whatever it is, good or bad, I just want to know," sighs Davis, who answers her door with tears streaming down her face. "I need closure."

Davis has raised her grandson, Deangelo, since he was six weeks old. He was the third child to vanish, and has been missing more than four months now.

Davis' carefully kept home is covered in yellow ribbons. Her grandson's room is perfectly arranged, a Care Bear stuffed animal on the bed and photo of teen rapper Lil' Romeo on the wall. The radio blasts through the house. If there is any news, Davis wants to hear it.

She works to keep her composure, but anything can set it off, like the other day, as she worked on the trinkets she sells to tourists at the nearby Straw Market. Her grandson used to help her with this.

"I was sitting there, just picturing him next to me cutting [the straw ends] off," she recalls. "And the tears just began to flow."

Another mother, Grant, has lived with this agony the longest. Her son Jake was the first to disappear. To believe her son is dead, Grant says, is to believe the "devil's lies." God gets her through the day; the night is even harder.

"When night come, you can't sleep," she says. "And even if you doze, you wake up wondering how they are being treated."

Grant is very specific in the things she misses about her boy. She misses his morning kiss and hug, watching him iron his own school uniform just so. She misses fixing his four o'clock snack every day after school. She misses catching him in front of the mirror, shaking like a wild thing to his favorite Calypso music.

She misses him climbing into her bed at night, blaming it on the fact that her room is the only one in their tiny apartment that has air conditioning.

Two of Grant's grown daughters are staying with her now, along with some grandchildren. The apartment only has two bedrooms, but no one can bear to use Jake's. It stays empty, waiting.

"They sleep here, on the floor," Grant says, motioning to a tiny empty patch of the living room.

Amid such an unreal situation, reality can seem tenuous. Grant recalls how one woman tried to comfort her, and within weeks, that woman's child had vanished too.

"She said, `Don't worry, they'll find them.' Not knowing she was next," Grant says, shaking her head. "Now her boy is gone too. I think I'm going crazy sometimes."

Claudette Mitchell, mother of the second boy to go missing, Mackinson Colas, has a very real reason to try and stay sane. Her belly swollen and hanging low, she is due to have a child in just one week.

"I have to stay strong for the baby," she says, her face full of exhaustion. "I hope it's a boy. My other son [Michael] misses Mackinson."

Mitchell is also racked with guilt. She is the one who sent her son to the store, the errand from which he never returned. "If I hadn't done that, none of this would have happened," she sighs.

Charline Smith, mother of the last boy to disappear, has the most hope. Her son has been gone about a week, and his disappearance was followed by an arrest. She thinks police must have strong leads.

Yet she and the other parents said police have told them little. Rather, they tell the parents not to believe the rumors, to keep hope, there is no evidence the boys are dead.

"It gives me a little relief to know they have somebody in custody, but I think there's more to do. I think there is a ring," she says. "I think they are gathering these kids to sell."

Sell for what? Her eyes cloud when she thinks of this. Her mind wanders as she sits in her home, a shack with concrete floors and plywood patched over the holes in the walls.

She does not answer the question.

"I am alive," she finally says, "but everything inside me is dead."

As despair builds on the island, so does anger. Increasingly, this normally close-knit community is looking within itself with suspicion.

"You used to trust everyone but now you can't trust anybody," says resident Daphne Nixon. "You don't know who's who. Somebody has to know something."

By Jamie Malernee, The Sun Sentinel