For decades, Mexican smugglers had exported homegrown marijuana and heroin to the United States. But as the Colombian cocaine boom gathered momentum in the 1980s and U.S. law enforcement began patrolling the Caribbean, the Colombians went in search of an alternate route to the United States and discovered one in Mexico.

Initially, Mexican traffickers, like a pudgy 25-year-old airplane pilot named Miguel Angel Martínez, acted as independent contractors who were paid a fee by the Colombians to move their cargo. In 1986, the Guadalajara cartel dispatched Martínez to the Colombian port of Barranquilla, in the hope that someone might commission him to fly drugs up to Mexico.

But Martínez couldn’t find any takers and ended up languishing in Colombia for months, worrying that he had blown his big opportunity with the cartel. Eventually, he caught a commercial flight back to Mexico, and shortly thereafter, he was summoned to a meeting with Chapo, who was by then an underboss in the cartel. “You were very well behaved in Colombia,” Chapo told him, according to subsequent testimony. He seemed impressed by Martínez’s patience in waiting for an assignment.

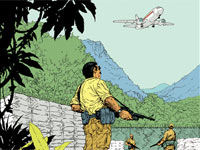

Having passed this test, Martínez started working for Chapo as a kind of air traffic controller, negotiating directly with the Cali and Medellín cartels, then guiding their cocaine flights from South America to secret runways in barren stretches of Mexico. Martínez knew U.S. agents were monitoring his radio communications, so rather than say a word, he would whistle — a signal to the pilots that they were cleared for takeoff.

With the decline of the Caribbean route, the Colombians started paying Mexican smugglers not in cash but in cocaine. More than any other factor, it was this transition that realigned the power dynamics along the narcotics supply chain in the Americas, because it allowed the Mexicans to stop serving as logistical middlemen and invest in their own drugs instead.