Moments of experience become a single extended second and in it one begins to hear what one sees- the swish of the garment in Big Mama, the cry of the artist Christ in Persecution Salvation, the pulling together of the female and male in Forgiveness, the parting of the wind as the Dancer moves to occupy his space. It is then, only then, when one can psychically experience this sonic transmogrification, that one realizes that this experience is only possible because Roberts has brought all he has to this work and left it there.

The exhibition's title indicates that Roberts is attempting to share with his audience, literally, the full range of his oeuvre in terms of creative processes and media. The assemblage of this body of work came as a result of Roberts' own soul searching as he grappled with  the National Art Gallery's request earlier this year for artists to submit their strongest work for possible inclusion in the Inaugural National Exhibition. When given such a challenge, how does the artist conceptualize him or herself? How does one begin to evaluate one's lifework and make a living will and testament with regards to one's art? Roberts' response was to explore his technical range through the subjects and themes he has become known for: Bahamian folklore, social conditions, women and families, the Bahamian landscape's beauty and simultaneous destruction, and spiritual wars and redemption. The processes of creation- carving, painting, drawing etc., now become the content of the work as much as his well-known subjects and themes. In such a conceptual inversion, the artist discovers and releases the inner force of his materials and moves from the representational to the non-objective with tangible results.

the National Art Gallery's request earlier this year for artists to submit their strongest work for possible inclusion in the Inaugural National Exhibition. When given such a challenge, how does the artist conceptualize him or herself? How does one begin to evaluate one's lifework and make a living will and testament with regards to one's art? Roberts' response was to explore his technical range through the subjects and themes he has become known for: Bahamian folklore, social conditions, women and families, the Bahamian landscape's beauty and simultaneous destruction, and spiritual wars and redemption. The processes of creation- carving, painting, drawing etc., now become the content of the work as much as his well-known subjects and themes. In such a conceptual inversion, the artist discovers and releases the inner force of his materials and moves from the representational to the non-objective with tangible results.

Roberts has become well known for his expressionistic painting style where he begins by remaking the void of creation, then pulling his imagery from a chaotic field of thickly applied textured paint. This approach is evidenced in this exhibition in the paintings Candlelight Vigil I and II, completed after the September 11th tragedy. In these works the pink and beige tones inhabit the energy of the process, performing what Patricia Glinton Meicholas has described as a cosmic dance, while providing a human connection with the spiritual transition that occurred that day.

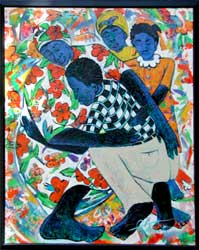

The subtlety of these paintings is in stark contrast with works such as Catch of the Day and Forgiveness, one of the exhibitions strongest offerings. In this composition, a mother-like figure in a fierce embrace with her errant son/husband occupies the center of the frame, while two girl children, possibly hers, possibly theirs, reach into the pair extending the circle. While there is a strong reference to the parable of the Prodigal Son, within the context of a matrifocal Bahamas, a sweet, straightforward reading of the work is disturbed. Gender is reassigned in this socio-cultural context where the son/husband now returns to the bosom of his mother/wife rather than that of the Biblical referent of the clearly defined and defining father. This fluidity of gender roles, generations and relations (with a light Oedipal veil) is possible partly because of the artist's re-presentation of the physically ample woman, a fixture in the tourist marketing strategy for these islands for many years. Normally assigned the role of an aged, husbandless, sex deprived mammy in that context, it can be argued that this ample bodied figure- for better or worse- has become typical of Bahamian women young and old, making it difficult to fix her as mother or wife.

The subtlety of these paintings is in stark contrast with works such as Catch of the Day and Forgiveness, one of the exhibitions strongest offerings. In this composition, a mother-like figure in a fierce embrace with her errant son/husband occupies the center of the frame, while two girl children, possibly hers, possibly theirs, reach into the pair extending the circle. While there is a strong reference to the parable of the Prodigal Son, within the context of a matrifocal Bahamas, a sweet, straightforward reading of the work is disturbed. Gender is reassigned in this socio-cultural context where the son/husband now returns to the bosom of his mother/wife rather than that of the Biblical referent of the clearly defined and defining father. This fluidity of gender roles, generations and relations (with a light Oedipal veil) is possible partly because of the artist's re-presentation of the physically ample woman, a fixture in the tourist marketing strategy for these islands for many years. Normally assigned the role of an aged, husbandless, sex deprived mammy in that context, it can be argued that this ample bodied figure- for better or worse- has become typical of Bahamian women young and old, making it difficult to fix her as mother or wife.

Formally in Forgiveness Roberts is at his best, flattening and collapsing planes and space, evincing gorgeous passages of color particularly in mother/wife's feet and arms, and powerful patterns and shapes that hold the surface of the painting. The cacophony of color and flowers enveloping the figures, is tempered here both formally and narratively by the blues of the their skin. Intense and complicated relations are expressed in the work. The visual connects to the audience at the level of emotion.

This sensory transfusion is particularly strong in Roberts' sculptural works. Looking at the drawings in the exhibition, it is remarkable how the sculptural process has infiltrated his handling of the media. The drawing tool is used almost as a raw carving tool, insistent and sure. But it is in the medium of wood, and in Roberts's attempts to combine wood with metal and stone, as in the work Crucifix (A collaboration with Tyrone Ferguson) and Reclining Figure (Olympia) that he truly raises the stakes for his audience.

Because of the materials used, the artist's handling of the form, and the way its art historical references intertwine so completely with the cultural context of its making, one can only describe Reclining Figure (Olympia) as a tour de force. Made from the bleeding wood of  Madeira, this reclining decapitated, scarred, grotesque, decomposing, emaciated, beautiful, vulnerable and compromised female form preens for her audience from a place on the edge of a post-modern cyborg abyss. Breastless, she denies those that look upon her body, expectations of the stereotypically nurturing female form. Instead her useless gesturally rendered hands simultaneously and savagely affirms her incapacity to exist beyond the offering of her sex. Made of indigenous wood and propped on iron casings, hewn and shaped outside of The Bahamas, the work becomes a signifier of the complex and costly interpolation of this country's economic progress with its natural and human resources.

Madeira, this reclining decapitated, scarred, grotesque, decomposing, emaciated, beautiful, vulnerable and compromised female form preens for her audience from a place on the edge of a post-modern cyborg abyss. Breastless, she denies those that look upon her body, expectations of the stereotypically nurturing female form. Instead her useless gesturally rendered hands simultaneously and savagely affirms her incapacity to exist beyond the offering of her sex. Made of indigenous wood and propped on iron casings, hewn and shaped outside of The Bahamas, the work becomes a signifier of the complex and costly interpolation of this country's economic progress with its natural and human resources.

However, Roberts does not leave us on the edge of Olympia's abyss, he pulls his audience back with works such as the spare, gestural, elegant and rich mocha coloured Ms. Duncombe and constantly demonstrates his facility in this medium by letting let the warm wood play a role in its resurrection. This attention to natural form and its subsequent contribution to narrative content are particularly evident in the works Heart Unfurled II and Big Mama.

In Heart Unfurled II, circles of the wood radiate from a "wounded" eye, shadowed like a birthmark to encompass the figures entire face. Roberts' attention to these memory marks in his composition is reminiscent of the great Jamaican sculptor Ronald Moody who believed that the spirit of the wood radiated through its rings. Roberts, like Moody, appears to consciously utilize the power center where the rings begin, as an experiential entrance point between the work and the viewer. In this context the sculpture reads as a figure emerging from a cocoon with a history that began in a wounding: The story of the African presence in the Caribbean.

Though the vulnerability present in Heart Unfurled is absent for the most part in Big Mama. In her massive, almost ubiquitous Bahamian form, her gentle yet commanding sway and with a face whose mouth appears to be in the middle of a good suck teeth, Roberts manages what can only be described as a loving touch, as the rippled imperfection, or character of the wood is transformed into the lip of a garment. The choices the artist makes in his process results in a covering for Big Mama while at the same time becoming a form itself, an artifact of the artistic will and experience. This conscious execution and technical effect recalls the goals of Greek Hellenistic sculpture most famously demonstrated in the work Victory of Samothrace currently in the Louvre. This style was developed in a period when artists were being encouraged to create sensuous life like sculpture that simultaneously communicated the most intense dramatic and emotional moments. Roberts nods at this classical tradition while producing a form that is truly Bahamian.

Antonius Roberts' range of references, media and processes reinforces the Bahamas' location as global crossroad. The potential for artists to take in and process different traditions in the context of this country's cultural rhythm is great. However, it can be argued that very few artists are truly utilizing the resources available to them in connection with the society in which they live, preferring to mimic nature, or transcribe an imagined and overly sentimentalized view firmly fixed on the past.

The Bahamas is a deeply spiritual place, a place of the seen and unseen. It is a culture that for better, or worse is being transformed physically, threatened environmentally, decimated socially, intellectually spent and engaged in spiritual and psychological warfare. In a society such as this, regurgitating tried and true images is almost meaningless. It is not art of its time.

With this assemblage of work Roberts expresses a realization that as an artist he cannot wait for others to provide him with templates for his work, nor can he wait for others to clarify his vision in the context of Bahamian society. His role as an artist is to step forward and face the prospect of "persecution or salvation" on a daily basis with the hope that someday others will come along.

Review By Erica James, Curator of the National Gallery of The Bahamas